What is a Graph?

A Graph is one of the most fundamental but also diverse data structures in computer science. A Graph consists of a set of vertices \(V\) and a set of edges \(E\) where each edge is an unordered pair. Hence, \(G=(V,E)\). They are used to represent relationships between various entities or elements (the vertices) by connecting them with edges. We denote an edge between two vertices \(u\) and \(v\) as \(\{u,v\}\). We then say that \(u\) and \(v\) are adjacent or neighbors and that the edge is incident to \(u\) and \(v\). Notice that the relation of two vertices being adjacent is an equivalence relation, so it is reflexive, symmetric and transitive. For simplicity in the beginning, we will not allow multiple edges between two vertices or self-loops, so no edge \(\{u,u\}\).

For example, a graph can be used to represent a social network where the vertices are people and the edges represent whether they are friends with each other or not, no edge signifying that they are not friends. In the below graph \(G=(V,E)\) where:

- \(V=\{\text{Bob, Alice, Michael, Urs, Karen}\}\) and

- \(E=\{\{1,2\},\{1,3\},\{2,4\},\{2,5\}\}\)

We can analyze the above graph and define some properties of it:

- Order: The order of a graph is the number of vertices in the graph. So in the above example, the order of the graph is 5. So it could also be called an order-5 graph.

- Degree: The degree of a vertex is the number of edges connected to that vertex. We denote the degree of a vertex \(v\) as \(\text{deg}(v)\). So in the above example, \(\text{deg(Alice)}=3\) and therefore Alice has the most friends in this social network.

- Isolated Vertex: A vertex with degree 0 is called an isolated vertex. So it is a vertex that is not connected to any other vertex and is therefore isolated. In the above example, John is an isolated vertex.

Handshaking Lemma

The handshaking lemma is a simple but important theorem in graph theory that if you think about it makes sense. The handshaking lemma says that the sum of the degrees of all the vertices in a graph is equal to twice the number of edges in the graph. So more formally:

\[\sum_{v \in V} \text{deg}(v) = 2|E| \]The intuition behind this is that each edge connects two vertices, so it contributes 1 to the degree of the two vertices. You can also imagine it as a handshake, hence the name. So each vertex is a person an edge is then that person stretching out their arm to the middle and the other person (vertex) doing the same and then they shake hands. So for each handshake (edge) two people need to strech out their arm (degree).

Average Degree

average degree is always \(2|E|/|V|\). This is because the sum of the degrees of all the vertices is equal to \(2|E|\) from the Handshaking Lemma. This also means that there are vertices \(x,y \in V\) such that \(\text{deg}(x) \geq 2|E|/|V|\) and \(\text{deg}(y) \leq 2|E|/|V|\).

Number of Uneven Degrees

The number of vertices with an uneven degree is always even. This is because the sum of the degrees of all the vertices is even from the Handshaking Lemma.

\[\sum_{v \in V} \text{deg}(v) = 2|E| = \sum_{v \in V_{\text{even}}} \text{deg}(v) + \sum_{v \in V_{\text{odd}}} \text{deg}(v) \]k-Regular Graphs

A k-regular graph is a graph where each vertex has the same degree \(k\). So all vertices have the same number of edges connected to them.

Networks vs Graphs

The title of this section is “Graphs and Networks” and commonly these two terms are used interchangeably so what is a Network and what is the difference between a Network and a Graph? Turns out its not much. The only real difference between a network and a graph is the terminology. A network is a graph with a real-world context. For example, a social network is a graph with a real-world context. A graph is a mathematical structure that represents relationships between objects.

When talking about a network we also tend to talk about nodes and links instead of vertices and edges. There is also an article here that goes into more detail about the differences between the two.

| Graphs | Networks |

|---|---|

| Vertices | Nodes |

| Edges | Links |

Graphs of Functions

When starting to learn about graphs, you might have thought about a different type of graph. You most likely visualized a Cartesian plane with x and y axes and a line or curve representing a function, so a graph of a function. This is very different from the graph we have been talking about so far. So what is a graph of a function? In mathematics, a Graph of a Function is a visual representation of the relationship between the input values (domain) and their corresponding output values (range) under a specific function. Graphs of Functions play a crucial role in analyzing and understanding the behavior of functions and studying their overall patterns and trends.

Formally, a Graph of a Function can be defined as follows:

Let \(f\) be a function defined on a set of input values, called the domain \(D\), and taking values in a set of output values, called the range \(R\). The Graph of the Function \(f\), denoted as \(G(f)\), is a mathematical representation consisting of a set of ordered pairs \((x, y)\), where \(x \in D\) and \(y = f(x)\). Each ordered pair represents a point on the graph, with \(x\) as the independent variable (input) and \(y\) as the dependent variable (output).

In other words, the Graph of a Function is a visual representation of how the elements in the domain are mapped to the corresponding elements in the range through the function \(f\).

Consider the following function:

\[f(x) = 2x + 1 \]Its domain could be the set of all real numbers \(\Bbb{R}\), and its range could also be \(\Bbb{R}\). To represent this function graphically, we plot points on the Cartesian plane where the \(x\)-coordinate corresponds to the input value, and the \(y\)-coordinate is the output value obtained by evaluating \(f(x)\).

Directed Graphs

In the graph the vertices were just connected by edges, the edges did not have a direction. This is called an undirected graph. Now we will look at the opposite, a directed graph.

A Directed Graph is a graph where each edge is directed from one vertex to another. In other words, the edges have a direction. The previous graph was an example of an undirected graph as we would hope that if person A thinks of person B as a friend then Person B feels the same way. However, in a directed graph, this is not necessarily the case.

So we can define a directed graph as \(G=(V,E)\) where:

- \(V\) is again the set of vertices

- \(E\) is a set of ordered pairs of vertices, called arcs, arrows or directed edges (sometimes simply edges). Ordered pairs are used here because (unlike for undirected graphs) the direction of an edge \((u,v)\) is important: \((u,v)\) is not the same edge as \((v,u)\) whereas for an undirected graph the edges \(\{u,v\}\) and \(\{v,u\}\) are the same edge matching the common mathmatical definition of sets and tuples. The first vertex in the edge, so where the edge starts, is called the tail, direct predecessor or initial vertex. The second vertex where the arrow head or point is, is called the head, direct successor or terminal vertex.

For example, let us imagine a directed graph where the vertices are the same as the previous example but the edges signify if a person has liked another person’s post on social media. We then get the below graph \(G=(V,E)\) where:

- \(V=\{\text{Bob, Alice, Michael, Urs, Karen}\}\) and

- \(E=\{(1,2),(1,3),(2,4),(2,5),(5,2)\}\)

When talking about degrees in a directed graph, we often distinguish between the in-degree and out-degree of a vertex:

- In-degree: The in-degree of a vertex is the number of edges that are pointing to that vertex. This is commonly denoted as \(\text{deg}_{\text{in}}(v)\). So in the above example, \(\text{deg}_{\text{in}}(\text{Alice})=2\).

- Out-degree: The out-degree of a vertex is the number of edges that are pointing away from that vertex. This is commonly denoted as \(\text{deg}_{\text{out}}(v)\). So in the above example, \(\text{deg}_{\text{out}}(\text{Alice})=2\).

These two new definitions also lead us to the definition of some new types of vertices like in the undirected graph we had isolated vertices, in the directed graph we have:

- Source Vertices: A source vertex is a vertex with an in-degree of 0. So it is a vertex that from which edges are only “flowing” out of. In the above example, Bob is a source vertex.

- Sink Vertices: A sink vertex is a vertex with an out-degree of 0. So it is a vertex that edges are only “flowing” into. In the above example, Urs and Michael are sink vertices.

Weighted Graphs

A weighted graph is a graph where each edge has a weight (a number associated with it). Commonly this is defined as a triple \(G = (E, V, w)\) where \(w\) is a function that maps edges or directed edges to their weights. So, \(w: E \rightarrow \Bbb{R}\) could be a function for a graph with real numbers as weights. The previous graphs were unweighted graphs, but we can easily think of them as being a weighted graph, where all weights are 1.

For example, in a graph where each city is a vertex and each edge is a road between two cities, the weight could be the distance in km between them.

Subgraphs

define what is a subgraph. then also use this below to define connected components, paths and cycles etc.

Induced Subgraphs

An induced subgraph is a subgraph that is formed by taking a subset of the vertices and all the edges that are incident to those vertices in the original graph.

Walks, Paths and Cycles

Graphs have many different use cases but a common one is to represent a network for transportation. So if we imagine a vertex as a house and an edge as a gravel path between two houses, then we can travel around the graph. This leads us to some important definitions in graph theory that are heavily used in algorithms.

Let’s start of with a walk, quiet literally. We define a walk as a sequence of vertices where there is an edge between each pair of consecutive vertices. So if we think of the gravel path between the houses, then a walk would be a sequence of houses that we can visit by following the gravel path. More formally:

A sequence of vertices \((v_1, v_2, \ldots, v_k)\) with \(v_i \in V \forall i\) is called a walk if there is an edge \(\{v_i, v_{i+1}\} \in E\) for all \(0 \leq i < k\).

This also leads us to being able to say that a vertex is reachable from another vertex if there is a walk between them. The length of a walk is the number of edges in the walk. So if the walk is \((v_1, v_2, \ldots, v_k)\) then the length of the walk is \(k-1\). If we started our walk at our own house in the morning and then returned to our house in the evening, then the first and last vertex would be the same. This is called a closed walk. More formally:

A sequence of vertices \((v_1, v_2, \ldots, v_k)\) is a closed walk if it is a walk \(3 \leq k\) and \(v_1 = v_k\).

We say that a closed walk needs to have at least 3 vertices as a closed walk with only 2 vertices would be our house to our house which isn’t exactly a good walk for our health. We can also observe in a closed walk that the start and end vertex are incident to an even number of edges. This makes sense as we need to exit and enter the vertex an even number of times. Notice also that on a walk or a closed walk we can visit the same vertex multiple times. So we can go from our house to the park and back to our house and then to the shop and back to our house. This changes when we look at a path. A path is a walk where we do not visit the same vertex twice. More formally:

A sequence of vertices \((v_1, v_2, \ldots, v_k)\) is a path if it is a walk and \(v_i \neq v_j\) for all \(i \neq j\).

So we never visit the same vertex twice, this also means that we never visit the same edge twice as if we did we would have to visit the same vertex twice. We can then also apply the same logic of a closed walk to a path to make a “closed path” which we call a cycle. More formally:

A sequence of vertices \((v_1, v_2, \ldots, v_k)\) is a cycle if it is a closed walk, \(4 \leq k\) and \(v_i \neq v_j\) for all \(i \neq j\).

The same definitions can be applied to directed graphs but now to be able to go from one vertex to another we need to follow the direction of the edges, if there is no edge with the correct direction then we cannot go from one vertex to another.

There are also trails and circuits which allow the same vertex to be visited multiple times but the same edge to only be used once.

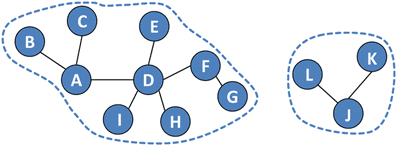

Connected Components

First we need to define what a subgraph is. A subgraph of a graph is a graph that is formed by taking a subset of the vertices and edges of the original graph. Meaning that a subgraph can be the original graph itself or it can be the original graph with some vertices and edges removed.

A connected component is then a special subgraph where all vertices are connected to each other. So There are no isolated/disconnected vertices in a connected component. These can quiet easily be seen by eye but the definition can become more complex when we look at directed graphs.

If a graph has only one connected component, so itself, then we say that it is connected. If it has more than one connected component, then it is disconnected.

Forms an equivalence relation on the vertices of the graph where the equivalence classes are the connected components. Two vertices s,t are related if there is an s-t path between them.

Undirected Graphs

In an undirected graph, a connected component is a subset of vertices such that there is a path between every pair of vertices in the subset.

If we think of a communication network, then a connected component would be a group of people that can communicate with each other. If there are multiple connected components, then there are groups of people that cannot communicate with each other.

To find the connected components of a undirected graph, we can simply use either a breadth-first search or a depth-first search over all vertices. The algorithm would then look something like this:

public int numberOfConnectedComponents(List<List<Integer>> graph) {

int n = graph.size();

boolean[] visited = new boolean[n];

int count = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

if (!visited[i]) {

dfs(graph, visited, i);

count++;

}

}

return count;

}Directed Graphs

In a directed graph the directions of the edges matter. This gives us two types of connected components, weakly connected components and strongly connected components.

Weakly Connected Components

Weakly connected components are the same as connected components in an undirected graphs. So you just ignore the directions of the edges.

In other words we look at the so called underlying graph of the directed graph. The underlying graph is the undirected graph that is formed by ignoring the directions of the edges in the directed graph. So if there is a directed edge from \(u\) to \(v\) then there is an edge between \(u\) and \(v\) in the underlying graph.

Strongly Connected Components

Strongly connected components are a bit more complex. In a directed graph, a strongly connected component is a subset of vertices such that there is a path between every pair of vertices in the subset, but the path must follow the direction of the edges. So in other words, after following the edges in the direction of the arrows, you must be able to get back to the original vertex.

Giant Components

If a connected component includes a large portion of the graph, then it is commonly referred to as a giant component. There is no strict definition of what a giant component is, but it is commonly used to refer to connected components that include more than 50% of the vertices in the graph.

Acyclic Graphs

An acyclic graph is a graph that contains no cycles. This means that there is no path that starts and ends at the same vertex. More formally:

A graph is acyclic if for every vertex \(v \in V\) there is no path from \(v\) to \(v\).

Acyclic graphs play a big role in computer science and many algorithms rely on the fact that the graph has no cycles. For example, a topological sort/ordering can only be done on a directed acyclic graph, short DAG.

Trees and Forests

A tree combines the properties of a connected graph and an acyclic graph, so it is an acyclic graph that has only one connected component and is therefore connected. This leads to the fact that there is only one path between any two vertices in a tree. If there were two paths between two vertices, then there would be a cycle in the graph and it would not be a tree.

Trees are used in many different algorithms and data structures such as binary search trees. You can read more the section dedicated to trees for more information.

A forest is a collection of trees so any graph that is acyclic as each connected component is then a tree.

Complete Graphs

A complete graph is a graph where each vertex is connected to every other vertex, very simple. In other words, a complete graph contains all possible edges which is why it is also commonly called a fully connected graph. A complete graph with \(n\) vertices is denoted as \(K_n\). If a graph has \(n\) vertices then the maximum number of edges it can have is defined as follows:

\[n-1 + n-2 + \ldots + 1 = \sum_{i=1}^{n-1} i = \frac{n(n-1)}{2} = \frac{|V|(|V|-1)}{2} \]The idea here is we start at one vertex and then connect it to all other vertices, then we move to the next vertex and connect it to all the other remaining vertices and so on until we have connected all vertices.

For example, the below graph is a complete graph with 5 vertices, \(K_5\).

Graph Density

Now that we know what a complete graph is and the maximum number of edges it can have, we can define the density of a graph. The density of a graph is the ratio of the number of edges to the number of possible edges. So in other words how densely connected the graph is or how close it is to being a complete graph. As the density of a graph is a ratio it can be between 0 and 1.

In an undirected graph, we have seen that there are \(\frac{|V|(|V|-1)}{2}\) possible edges. Which means the density of an undirected graph is defined as:

\[D = \frac{|E|}{\frac{|V|(|V|-1)}{2}} = \frac{2|E|}{|V|(|V|-1)} \]In a directed graph there are \(|V|(|V|-1)\) possible edges because each vertex can have an edge to every other vertex except itself due to the direction of the edges. So the density of a directed graph is:

\[D = \frac{|E|}{|V|(|V|-1)} \]